The presentation analyzes the prize contests of the Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences in the last three decades of the eighteenth century. The Society was founded by a handful of learned men employed by the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in Batavia (today’s Jakarta), inspired by the mushrooming of learned societies and academies in the Netherlands and Europe, and motivated by the perceived isolation from European culture. By adopting the modus operandi of Enlightenment learned societies, the Batavian Society not only promoted the collection of objects from Dutch colonial holdings and their surroundings but also encouraged the gathering of useful knowledge through prize contests, a popular academic genre in Europe.

Unlike the metropolis, where the primary focus was on philosophy, the colonial outpost prioritized practical knowledge. The questions concerned shipbuilding methods, the health of slaves in transit, caring for sick sailors once in Batavia, and so on. Initially, the contest was opened to other VOC members in Batavia and the Asian colonial outposts, but responses were few and unsatisfactory. Determined to make the contests a success, the Society sponsored three Dutch-based societies that held prize contests to ask similar questions, but even fewer responses were received due to the lack of knowledge about colonial issues. In a final attempt to make the contests relevant, the Society sponsored questions addressing local Dutch issues, such as Reformed education and the reconsideration of church burials.

The presentation will investigate why the founding members of the Batavian Society sought to emulate European learned societies in a colonial outpost and why they sponsored the prize contests in the Dutch Republic at a time when the VOC was going bankrupt. In doing so, it will argue, firstly, that European intellectual sociability during the Enlightenment became a criterion for self-identifying as civilized, especially among the Dutch mercantile classes and particularly in a non-European context. Secondly, it will demonstrate that useful knowledge was seen as a potential solution for the overall decay of the VOC and the perceived decline of the Dutch Republic, engaging learned men both in the metropolis and the colonies. Lastly, it will conceptualize the genre of colonial instructions by showing that prize questions were public-facing instructions, defined by utility and epistemological optimism.

Maria Florutau is a Postdoctoral Researcher on the Project Early Citizen Science at Uppsala University. She studies the transnational historian of European Enlightenment and is particularly interested in decentralising the circulation of knowledge across the continent from Eastern to Western Europe and back during the long eighteenth century, as well understanding the contributory nature of non-European thought on enlightened philosophy and culture. In the project, she examines the uptake of Linnaean instructions in the Netherlands and its colonies and in the Habsburg Empire. Maria completed a DPhil in Early Modern History at the University of Oxford (2022), having previously studied at University College London. She is currently revising her thesis, Transnational knowledge transfer in the Enlightenment (c.1750-1790): the case of József Fogarasi Pap, to be published with Oxford University Press.

The Instructing Colonial Natural History Seminar Series is organised by the Instructing Natural History Research Group, Uppsala University

To register for the Zoom link, please email instructingnaturalhistory@uu.se

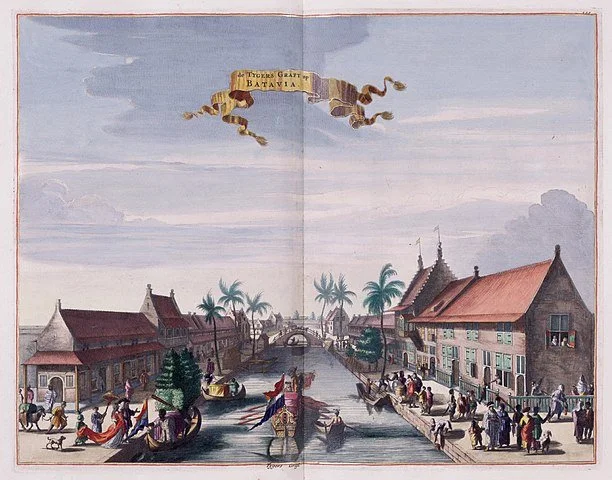

Image source: Gezicht op de Tijgersgracht te Batavia, 1682, Wikimedia Commons.